How Syria’s communication problem is feeding the conflict and preventing solutions

Thursday, February 26th, 2015 | A post by Camille Otrakji

Communication is the interchange of feelings, thoughts, opinions, or information by speech, writing, symbols, or through other non-verbal means. The way Syrians, as well as various non-Syrian stakeholders in the Syria crisis communicated, negatively and severely impacted the outcome of the movement for change that commenced in early 2011. This document will list a number of pre-crisis and post-crisis challenges, attitudes and behaviors that should, and hopefully could, be addressed or altered if the various parties that are active in the Syria crisis are genuinely seeking an end to the conflict.

Analysis | Pre Crisis

Months before the start of the unrest in Syria, “Reporters without borders” published their “2010 world press freedom index” that placed Syria at number 173 out of 178 nations on the list. The annual report warned that “press freedom [in Syria] is fast shrinking away”.

On the other hand, International “Freedom” indices are not calculated in a precise scientific manner. They are often biased political tools that some western governments find useful in applying pressure on other governments they prefer to weaken or change. Syria, therefore, was probably not one of the world’s 5 worst places for press freedom as the 2010 index report suggested.

Nevertheless, there was always a general agreement among most Syrians, including those who were satisfied overall with their leadership’s performance, that the country is not media-friendly. Syria had no truly Independent and commercially successful media outlets and everyone understood that there are limits very few were allowed to cross when expressing political opinions.

Because of the state of war with Israel and due to the frequent, if not constant attempts by Washington and its allies to weaken, challenge or even topple Syria’s leadership, a preference emerged in Damascus for ambiguity over clarity and for silence over talking. Communicating publicly or in private, meant potentially helping Syria’s enemies and adversaries better understand Syrian leadership’s psychology, intentions, capabilities, popularity or state of relations with Syria’s allies.

President Hafez Al-Assad used to be known as “the sphinx of Damascus” as he rarely spoke in public. He had a spokesman, Mr. Gebran Kouriyeh, but the public side of his job was limited to issuing a generic press release each time there was a visiting head of state. President Bashar Al-Assad communicated more often, but almost exclusively to western audiences. Until the start of the Arab Spring, neither President ever granted an interview to Syrian television.

In the rare cases when the President or other government officials formally and publicly communicated with the Syrian people, it was always a one-way process. A speech at Damascus University to declare we will not submit to the Bush administration’s hostile threats, or a speech at parliament after the President was re-elected. Always a speech, never a discussion like the ones the President and the first lady had with a number of French intellectuals during their visit to France in 2010.

Analysis | Post Crisis

Throughout the duration of the Syria crisis it has been clear that the disappointing state of communications in Syria is not only a product of government’s limitations of freedoms. Syrians were empowered through free technological tools to establish their own communication platforms on Facebook, Twitter, You Tube or blogs. But very often they focused, consciously or subconsciously, their activism on a set of negative objectives. This applies to Syrians living under government restrictions inside the country as well as to Syrians living outside, often for decades, in societies that enjoy considerably higher margins of freedom.

The problem is therefore more complex. At the individual, micro, level, there are perceptual and other psychological biases or deficiencies. At the societal level, there are flawed value systems and social habits that made it difficult to communicate effectively or constructively in an environment full of divergent views.

Few reliable professionals are communicating. Propagandists and other generally irresponsible communicators are highly active. Syrian government’s media sources tried but mostly failed to effectively promote the government’s narrative of the crisis, due to historic distrust of official media, its perceived lack of neutrality and professionalism. On the other hand, Arab and international media outlets were highly effective, until recently, in promoting their agenda. Aljazeera promoted Qatar’s and the Muslim Brotherhood’s agenda, Alarabiya promoted Saudi Arabia’s, the BBC, France24 (France) and CNN constantly tried to justify American military intervention in Syria. Western and Arab media generally played a reckless, arguably criminal, role in manufacturing anger and hate and sectarianism in Syria.

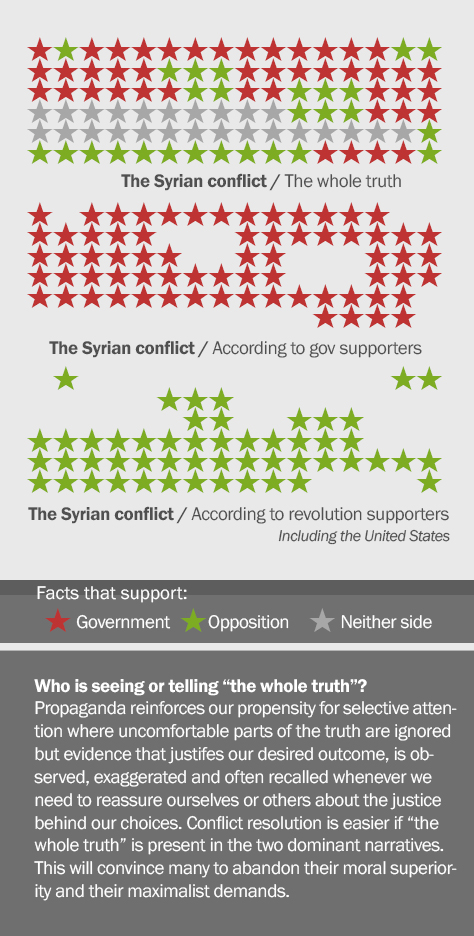

The massive volume and constant stream of information (news, opinion pieces, rumors and statistics) in addition to the various emotional factors influencing many of the Syria crisis information consumers (fear, anger, admiration, adulation, irrational expectations…) jointly led to a highly selective attention, processing, storage and recall to information related to the Syrian conflict. Details are dropped (due to fatigue and to time constraints). Non-pleasant news, opinions and information sources are avoided religiously.

Today, information consumers rely mostly on interactive, online, sources. This also made it easier for them to be highly selective since they can have much more control over content and sources, compared to the days of analogue TV or radio when it was less likely to skip or fast forward unpleasant opinions or information.

Because Syria’s population is young, and because non-Syrian activists who interact with the Syrian crisis also tend to be relatively young, short attention span is common. Few have patience to absorb the intricacies and complexities of the Syrian crisis. Those on Facebook prefer pictures, though some are willing to read a small number of paragraphs. Those on Twitter prefer slogans and one-liners. Three years into the crisis one gets the sense that very few learned, or moderated their initial views despite all the time they spent hopping from one piece of information to the other.

Syrian leadership/government learned from earlier Egyptian/Tunisian/Yemeni Arab Spring chapters that weakness only invites ridicule and that it would surely boost the sense of confidence of its adversaries. This led to a communication style that is lacking in understanding, compassion and empathy to anyone but government supporters.

The Syrian leadership’s distaste for, and lack of experience in, communicating contributed to a growing lack of trust in its intentions while the Arab Spring narrative proved increasingly convincing to Syria’s young activists who were eager to play a role that would lead to more vivid results. At a time when Egypt and Tunisia appeared like success stories where change was popular, possible, efficient and safe, Syrian leadership sounded hesitant, slow, and opaque. President Assad’s March 2011 speech was roundly criticized for a number of reasons. Most criticism targeted the excessive display of adulation by many members of parliament, but perhaps the most damaging aspect of the speech was the continued lack of clarity at a time when people were expecting their leadership to treat them as partners in decision making. The impression left was that this is a one-way speech to tell us “we know best what’s good for Syria. This is bigger than your small Arab Spring ideals. Stay out of it, trust us there is a big conspiracy”.

Opposition and its community of Syrian and non-Syrian supporters (including most foreign analysts and journalists) had the initial, “Arab spring” inspired, expectation that the regime does not represent the people and that it will therefore be quickly and surely defeated by “the people”. This Led to a total boycott on their side of the regime supporting (or tolerating) camp. They would not listen to, interview, read, or debate regime supporters. In the rare cases where there was communication, it was usually accompanied with condescension, antipathy and lack of trust or respect.

Aside form any genuine movement for change, there was also a well financed regime change operation that had no interest in communicating the truth. High-priced public relations professionals were hired. Activists wanting to tell their propagandist fairy-tale narrative had help from graphic designers to video editors to communication specialists. The more polished their communication products appeared, the more convinced they were with the distorted narrative they contributed to. The lies and distortions from the revolution supporting side of the conflict exceeded by far the wildest propaganda efforts from the government’s side

What can be done?

Dr. Phillip Zimbardo who conducted a Stanford University prison experiment, later described the seven steps of “the slippery slope to evil”. The process that takes good people through the permeable line that separates good from evil behaviors.

1. Mindlessly taking the first small step.

2. Dehumanization of others.

3. De-individuation of self.

4. Diffusion of Personal Responsibility

5. Blind obedience to authority

6. Uncritical conformity to group norms.

7. Passive tolerance to evil through inaction or indifference.

The above steps should be dismantled through a carefully-planned communication process. The different parties to the Syrian conflict need to agree to commit to the de-escalation process. Governments (Syrian and others), opposition figures, the army, media (state controlled and independent), activists on social media, and NGOs need to understand their respective responsibilities in ending the cycle of violence.

Articles 19 and 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights say:

Article 19

The exercise of the [freedom of expression] rights carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions:

(a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others;

(b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.

Article 20

1. Any propaganda for war shall be prohibited by law.

2. Any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law.

Social media as well as traditional media are full of daily widespread violations of the above articles. Propaganda for war and incitement to hostility against religious groups are very common. De-escalation can accelerate the success rate of efforts to stop the conflict. While a general agreement for ending the military conflict might not be within the compass of peace-makers’ attainment, a more limited agreement on rules that govern the way all are communicating the Syrian crisis should not be beyond reach.

__________________________

Camille Otrakji is the founder of a number of online dialogue initiatives. He won the 2012 Excellence in Research Award for best scientific research in the International journal of Information Systems and Social Change (IJISSC)

CreativeSyria

CreativeSyria

Comments (0)

There are no comments for this post so far.

Post a comment